Berger

Between Human And Animal

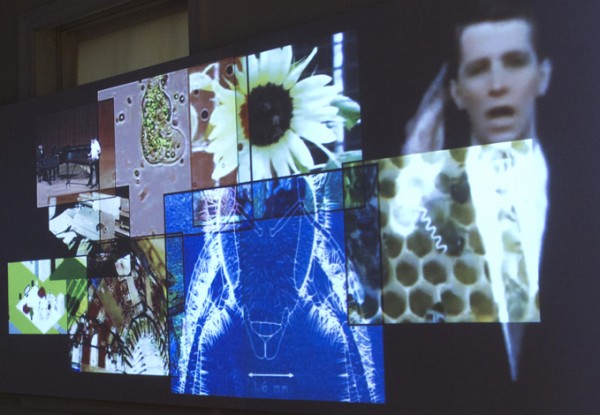

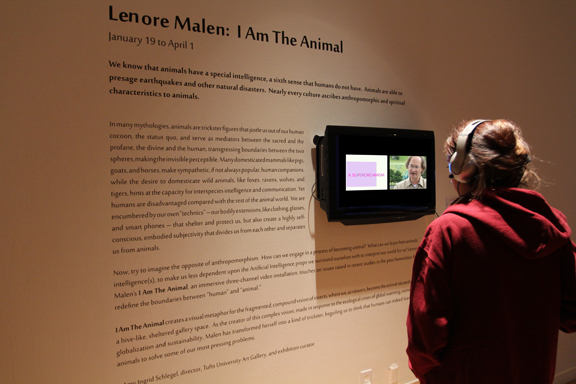

On Wednesday March 28th, 2012 Tufts University hosted a conference titled Between Human and Animal. The panel focused on my video installation, I Am The Animal which was on view at the time, but it also touched on many other things.

Here’s a synopsis:

Through the lens of artist Lenore Malen’s installation, I Am The Animal, and mindful of the ecological and political challenges we face today, three cultural theorists, Jill Constantino, Susan McHugh, and Kari Weil, will consider the animal as a philosophical, ethical, and biopolitical subject. Moving beyond Western traditions of humanism and the enlightenment the panelists will also share their ideas on rethinking the boundaries between living species and other forms of matter. Malen will discuss media from the viewpoint of the animal: “Displacing and transposing notions of nature and technology.”

You can read the talks in essay form here. Kari Weil is Professor of Letters at Wesleyan University. Her new book, Thinking Animals was published in March 2012 by Columbia University Press.

Lenore Malen: I Am The Animal by Kari Weil

The week before last I was in Paris for spring break, staying in an apartment near the Bastille. It just so happened that right across from the apartment where I was staying, there was an “apiculture” shop—something I had never seen before. It was filled with books about bees, information about honey, and products made from honey; the window had a big poster that said, “Penser l’abeille” (“Think bee”). Of course, the fact that interest in bees has spread across the Atlantic, if not beyond, is not surprising, given the widespread media attention to colony collapse and the fear invoked at the end of Lenore’s video—that, unlike rats and various microbes which seem to be able fight back and withstand the immense destruction of their environments by adapting to them, bees may not be similarly well equipped. Will they outlast us or will we, rather, be their death? This question has inspired much work in animal studies over the past decades, although it is perhaps only recently that insects, and bees in particular, have been included in this concern. The idea that the loss of animals is the impetus behind our “modern” failed attempts to reintegrate them into our lives was the thesis of a now classic text of animal studies, John Berger’s Why Look at Animals? Until the eighteenth-century, Berger suggests, we lived with animals (whether combatively or symbiotically) and experienced them not only as suppliers of food (think honey) and clothing, but more important, as mortal, sentient beings whose different yet parallel lives offered the possibility of imagining nonhuman subjectivity. Since that time we have developed a range of practices to try to compensate for this loss: pet-keeping, zoos, even Disney cartoons—practices, he argues, that rather than bring us any closer to non human subjectivity only distance us from any true engagement with animals. Should we include beekeeping among such practices, especially now that hives have been installed, not only in backyards but atop the Paris Opera, the Tate Galleries in London, and the Whitney Museum in New York? Or are bees among those animals who defy any easy separation between animal-nature and human-culture? Adding to the list of practices that, Berger says, only de-nature animals, he includes certain photographic techniques that reveal the most furtive species to the curiosity of the human eye but leave them as objects of a human gaze. “The fact that they can observe us,” he says, “has lost all significance.” Putting Lenore’s installation in dialogue with Berger, we might want to ask, can the camera reveal the gaze of the bee? Her film answers with a smarter question, or even a series of them. Is subjectivity confined to the gaze? Is it only by invoking the point of view of the animal that his or her subjectivity can be invoked? Might that not be an impoverished understanding of subjectivity?

Indeed, this identification between subjectivity and the act of looking may be a shortcoming in Berger if not in Derrida, whose text Lenore invokes throughout her piece. It is, of course, in noticing his female cat looking at him that Derrida remembers she has her own “point of view,” one, however, that he understands he may not be able to grasp or comprehend. And yet it is this encounter with the animal/otherness that, for Derrida, reveals our own human incapacities, our vulnerabilities by stripping us of those clothes and technologies by which we have falsely imagined our ability to lay claim to our difference or justified our domination. And it is thus in that encounter that, he says, thinking itself may begin. “The animal looks at us, and we are naked before it. Thinking perhaps begins there” (The Animal That Therefore I Am, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008: 29).

“I am the animal,” Lenore’s title boldly proclaims, as if her video-camera were to effect a kind of “thinking bee” that throws into question what this thinking is that has been said to be the property of humans alone. Derrida’s title The Animal That Therefore I Am—although the original title, L’animal que, donc, je suis, can be translated as “. . . That Therefore I Follow:)—must, of course, be heard as following Descartes’s “I think therefore I am,” replacing the “I think” with “the animal that,” thereby challenging his philosophical predecessor, who denied animals the ability to think. For Descartes, animals were machines that could only react to stimuli as if from a mechanical principle, not with anything even resembling thought or consciousness.

Lenore’s “I am the animal,” is, of course, a hybridized “I” partaking of, while representing human, animal and machine. It demonstrates how we humans have become dependent upon the machine as a kind of prosthetic for our thinking. As Lenore writes, “For humans, inventions take place outside our bodies, whereas for bees, their bodies are their inventions, made and remade with the wax that extrudes from their abdomens.” It is thus easy for us to become estranged from our inventions as from our thinking, and such alienation is part of the double or really triple movement of Lenore’s film. In early frames we see scientists building boxes, methodically laying out sheets or painting spots on bees for some sort of experiments we are not privy to. Alongside these experiments we are presented with noises and music and images that seem to have nothing to do with bees—xylophones, tap dancing, the “tap tap tap” of something between toy and instrument, Fred Astaire singing “Night and Day”—each happening undercutting the goal-oriented projects of science by revealing the propensities for “unproductive” or unpurposive rhythm and duration that intrude at their core, turning calculation to confection. Is this animality infecting the projects of culture? Or is it culture that turns mechanical animality away from any necessary relation with utility? The eye/I of the video renders the answer undecidable.

One of the effects of such repetitive sounds is to “deterritorialize” (in the Deleuzian sense) vision—to liberate it from its conceptual framework and render it incapable of picturing the world as an object of knowledge. What, in fact, we must ask, can vision reveal of the worlds or Umwelten of bees, which, we are reminded early on, consist greatly of smell? Can we see what the bees smell? Can we see the difference between fear and love that they detect in a smell? This poverty of our vision is highlighted by the unclear connections between images or between images and sounds. We humans demand a supplement in the form of another prosthesis—text, writing—to clarify what it is we are seeing. But when this text appears in Lenore’s piece, it moves quickly, joining the mechanical reeling of the video. I wanted to slow it down or stop it so I could read, so I could understand and say, Ah ha! Is this what Derrida means when he writes, “Man is less a beast of prey than a beast that is prey to language”(121)? It is interesting for our purposes here to note that this is a comment Derrida makes in his essay on Jacques Lacan, and specifically in response to Lacan’s take on the work of Karl von Frisch and the language of bees. I quote Derrida:

Lacan claims to be relying on what he blithely calls the “animal kingdom” in order to critique the current notion of “language as a sign” as opposed to “human languages.” When bees appear to “respond” to a “message,” they do not respond but react; they merely obey a fixed program, whereas the human subject responds to the other, to the question from or of the other. This discourse is quite literally Cartesian(123).

But why, we should ask on a first level, should language be taken as the index of thought or consciousness except that we take it as such for humans? Couldn’t we say that this view of language and, by extension, of our difference from animals is itself determined by a fixed, if not inescapable anthropocentrism rather than by any real response on our part. Indeed, and more important, why should we demand a response from the other as the condition for our responding to them? This may be another way of interpreting who follows whom. For if I will only respond to one whose language I recognize as such, am I not disavowing my responsibility to that very notion of the evocative, as opposed to the informative, that Lacan claims constitutes language? And why, above all, is it the other’s response to me and to my names that is at stake, rather than mine to the other? What if the animals are calling us but we can neither hear nor read them? What if we humans simply do not respond?

Lenore’s video does not invite us into the language of bees or attempt to reveal their world to us. It defends itself against any suggestion that one could represent the language or point of view of a bee. Rather, it thinks with bees and, with machines and film and with other humans, to evoke an ongoing response, one, moreover, that is meaningful, but not because it is predicated on understanding or knowledge. What it evokes, rather, is the relay of response between bee, machine, and human such that the buzz of one affects the music of the other, which affects the rhythms that can be heard, the taps that can be danced or waltzed from day to night and back to day in a loop that may affect if not infect the science and the scientist with admiration more than knowledge.

“I am the animal,” Lenore announces in tandem with Derrida, who admits that “my animal figures multiply, gain in insistence and visibility, become active, swarm, mobilize and get motivated, move and become moved all the more as my texts become more explicitly autobiographical, are more uttered in the first person”(35). What is visible in the video, as it is in Derrida’s figures (and I would say unlike the texts of Deleuze or Agamben), is what Derrida calls the irreducible hetero-affection at the seat of the I—the imaginative capacity or vulnerability to be affected or moved by an other or other-animal that infects the very autonomy of the I and, with it, any simple delimitation between man and animal—or, in this case, woman, animal, and machine. It is in heter-affection that we viewers follow the animal-other and in step with the “beat beat beat” of the tom-tom.

To download the entire article as a PDF click here. Kari Weil RTF

Susan McHugh’s essay follows here.

Susan McHugh is Professor of Comparative Literature/ University of New England Animal Stories‑Narrating Across Species Lines was published in 2011 by the University of Minnnesota Press.

Image, Story, Crash: Lenore Malen’s I Am The Animal

You see interchangeable robots tugging a placid child across the room. You see dancers, some in bee costumes, so many fading in and out onscreen that their movements are hard to follow. You see cars parading symmetrically around a track in one image, and in another, repeated, a car crashes in a tunnel, then others pile up from behind, crashing in a chain reaction. All the while, in other corners of your field of vision, you try to follow stories of beekeepers who love, and appear to be losing, an animal with whom they are intimate, a companion species on whom we all rely for food. In this subtle way, the visual metaphors that build up to the crash image in Lenore Malen’s video installation I Am The Animal (2012) bring familiar notions of bees to where scientists and philosophers alike fear to tread: an acknowledgement of failure in our representations of honeybees, and a reorientation toward longing to live together.

In this characterization, students of philosophy will recognize Gilles Deleuze’s critique of representation in favor of a theory of life itself, which rejects the usual ontological premise of autonomous selves, individuals differentiated in opposition to masses of animals or things, and starts with the radically leveling proposition that life itself boils down to two things: desire and the social, or longing and living together. One difficulty of rising to Deleuze’s challenge is that it requires us to abandon the hierarchical dualisms through which we have learned to think of creation as separate from, and lesser than, ourselves. And another is that visualizing this new ontology rules out the possibility that the work of art is to illustrate philosophical points.

Through this creative theory, artist and art historian Steve Baker characterizes a distinctly contemporary artistic engagement with animal life that he characterizes in The Postmodern Animal in terms of an aesthetic of “botched taxidermy” that deliberately shows the seams, the bald spots, the imperfections or failures of representing animal life but that does not therefore constitute artistic failure. Rather than being “didactic or moralizing or sentimental,” he argues, this kind of animal art has its own integrity, does its own work to open up the ways in which people think about animals. And it involves what he calls in more recent work a “formal toughness,” signaled by artists’ “unflinching” gazes in “working with form, and not – to oversimplify – with sentiment-drenched content.” Ranging across forms my own book Animal Stories, I follow these developments across fine art and other visual media as well as literature to investigate more precisely what happens in acts of narrating what happens between humans and other animals, and I’m becoming increasingly fascinated with creative people’s stories of living with and learning from members of other species on the brink.

Like few contemporary artists, Malen follows honeybees through familiar explorations of alien and utopian aesthetics only with an intensely visual and unflinching contact with bees. I was not surprised to learn that she kept bees so much as that she did so at her own peril (as someone with a life-threatening allergy to them). This contact grounds an artistically unusually deep engagement with the unique communities of bees and beekeepers in I Am The Animal make visible a rupture in species hierarchies, and in so doing create a space in which to engage with the collective activity of a hive. Perhaps it’s worth noting, first and foremost, that hers is not the usual story of honeybees today, so often painted in the lurid shades of Colony Collapse Disorder or CCD.

A term first applied in 2006 to a phenomenon where workers of a hive disappear, causing the death of the colony, CCD is only one of many suspects in the drastic drop by the millions of hives worldwide. Amid so many pressures on this species, including the spread of known chronic diseases, intensive monocrop farming, widespread chemical use, genetically modified crop plants, and the shrinking gene pool of commercially-bred honeybees, this phenomenon with no clearly identified causes or cures is only one of the ways in which it is becoming apparent that along with honeybees the insect and avian pollinators of the world are dying, undergoing an unprecedented period of severe endangerment and extinction. Yet, in public discussions as well as in my own recent research into contemporary fiction, film, and fine art that revisits historical connections between mass killings of people and animals, I find a narrow focus on symptoms like CCD at the expense of cures like major overhauls in the business of agriculture, which would involve rethinking plants, animals, people and others not in terms of resources but as lives. This is where Malen’s visual figurations of contact between the species stand to make all the difference in the future of human life with (and maybe as) another species.

With her rootedness in the practice of beekeeping, Malen has less in common with honeybee-focused contemporary artists than with hybrid scholar-dog trainers like Vicki Hearne and Donna Haraway, who in recent decades have advanced theories of cross-species companionship only in the limited sphere of human-canine relations, where the antiquity and ubiquity of the relationship makes it arguably the case that our species is conceptually if not physically inseparable from theirs (at least, that’s what I claim in my book Dog). But can theories of cross-species companionship that are centered on the respect, reciprocity, and responsibility familiar to the ordinary harmonies of domestic life be extended to account for much more recent and rarified relations like those of humans and honeybees? As the stories of a “group soul” in Malen’s Beekeepers’ Tales (2012) indicate, such understandings necessarily involve not only engagements between people and bees but also among people who share the experience of trying to learn what it means to care for insect colonies in increasingly unlikely circumstances.

Like Malen, who has kept hives, I have a special interest in the one pollinator who is also our companion species, apis mellifera, or the European honeybee. As an undergraduate at a university then still clinging to its heritage as a land-grant institute, my favorite class was Practical Beekeeping, as a condition of which as students we had to submit to being stung in the university bee yard (none of us proved allergic). There I caught the bug, so to speak, and subsequently volunteered for a year as the Worcester County Honey Queen, traveling to fairs and trade shows to answer questions and otherwise promote understanding of honeybees and beekeeping. So I know firsthand that dramatically dropping numbers concern much more than just economic losses. As one of the interviewees in Beekeepers’ Tales, Victor Borghi asks, “How can I help these creatures?” And he’s referring not simply to his “eighty to ninety thousand bees” but to the species as a whole: “What can we do if they die?” While drawing from this same documentary-style material, I Am The Animal organizes it in a formally tougher way, one that purposefully collapses metaphorical and other distinctions between honeybees and humans.

Snippets of documentaries and dramas, musicals and music videos, as well as other materials sourced on the World Wide Web are enfolded to create a productive confusion that does more than just record the fragile and quite possibly doomed relationship between honeybees and people. As metaphors like robot and dancer collapse, I Am The Animal uproots the cherished truisms of bees as the perfect image of order, and makes room for the flourishing of emergent scientific and old-time keepers’ visions of bees as organized through nonhierarchic networks, both the folkloric group souls and the literal swarms that are central to this super-organism’s survival. According to another interviewee, biologist Tom Seeley, the capacity for distributed negotiation in the critical moment of together choosing a new home is the quality that makes swarming honeybees operate as “groups that are far smarter than the smartest individuals in them.” In his terms, swarm intelligence not only organizes a “honeybee democracy” but also mirrors that of brain neurons: bee visits, like neuron firings, compete to accumulate a quorum or critical level of support through which the system makes a choice. Popping in and out seemingly at random but leading to a distinct conclusion in I Am The Animal, the cacophonous visual presentation of metaphorical and other figures of honeybee life likewise enacts a deliberation rather than a displacement of viewpoints, and in so doing makes manifest the material as well as political implications for viewers thinking with honeybees.

For, at another level, this presentation takes viewers through a history in which the modern, mechanical metaphors of insect life give way to these new understandings of super-organisms like honeybees as agencies without centers. Media theorist Jussi Parikka (who contributed an essay to the exhibition catalog) argues further that this vision shapes interactions among humans through the new, swarmlike modes of radical politics grounded in multitudes rather than individuals that are rendered perhaps most visible today in flash-mob-style actions orchestrated through social media. What may be more difficult to grasp is how such actions are guided by “alternative logics of thought, organization, and sensation,” in Seeley’s model, the negotiation through confusion at the center of all of our thought processes, and what Malen evokes here in terms of the intensely disorienting sense of collective activity that confronts you when you first open up a beehive.

While it is possible to read I Am The Animal as a sort of immersion experience with becoming a bee—through which, for instance, the multiple, simultaneous, moving images might represent viewing the world through three simple eyes along with two compound eyes, each comprising thousands of lenses—this view that I have sketched of the installation instead as an expression of living with bees helps to explain what exactly sets this piece apart from other contemporary honeybee art (and I can talk about more examples later, if you like). For now, it may be enough to say that, amid these theoretical considerations, the cleverness or audacity—or intelligent outrage?—of Malen’s I Am The Animal becomes all the more astonishing.

Click here to download Susan’s essay as a PDF. McHugh essay on Malen

Jill Constantino discussed her anthropological field work on the Galapagos Islands—the so called Living Laboratory of Evolution, imagined as peopleless, but actually the home of 25,000 people, originally from the mainland of Ecuador.

The conference was organized by the curator and director of the galleries at Tufts, Amy Schlegel, with the assistance of Dorothée Perin. For me it was a great event and the culmination of a five -year project that began with a 2007 performance at the Cue Art Foundation titled Harmony As A Hive.

There’s an excellent review of the show in the Tufts Daily (Feb. 1st 2012) by Anna Majeska. Dreamlike Exhibit Throws Viewers Into Bees’ World. And here’s the link as a PDF: Dreamlike exhibit throws viewers into bees’ world – Tufts Daily – Tufts University.

1 Comment